On sharpening the saw

Vim users sit somewhere on a spectrum, based on how much they customize their editor. At one end of the spectrum, there are those who use Vim with no customizations whatsoever. At the other end are those who customize Vim to the point where it barely resembles the stock install.

Gary Bernhardt advocates using stock Vim, with very few customizations.

Vim is a chainsaw, and the last thing you want on a chainsaw is controls that are not the controls you’re used to, because then you will cut your hand off.

Gary Bernhardt on Ruby Rogues episode 40 (17:35)

Gary’s chainsaw metaphor warns against the practice of over-customizing Vim. But I would also warn against using Vim without any customizations. Vim is highly configurable, and some of the default settings are suboptimal. If you don’t have a basic vimrc, then you’re putting up with inconveniences that were fixed decades ago.

Vim is unlike other text editors

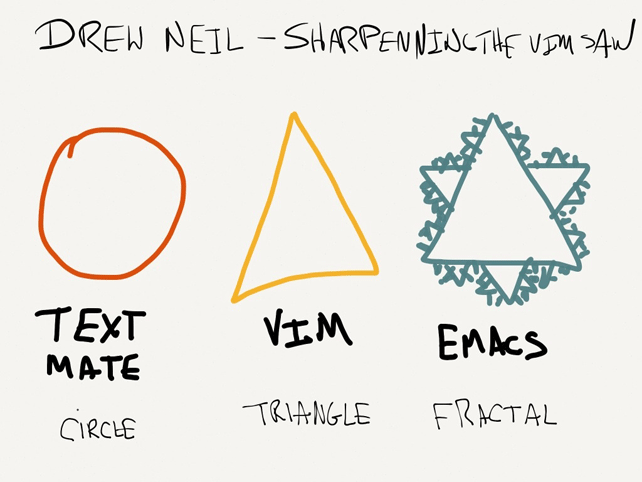

For the sake of illustration, I’d like to compare Vim with TextMate. I’m a recovering TextMate user, so I can speak about it with confidence, but you could probably s/TextMate/Sublime or s/TextMate/BBEdit and follow the discussion just as well.

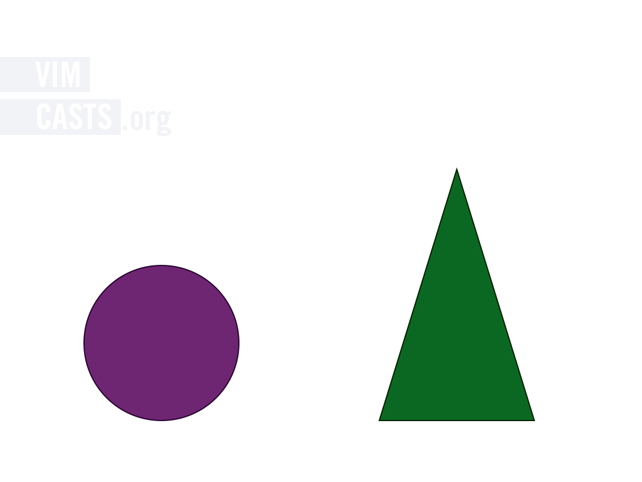

For an OS X user, the TextMate experience is consistent with expectations. It follows conventions of OS X, such as cmd-F to summon the find dialog, cmd-G to jump to next match, and cmd-E to search for the selected text. These all work in Safari too, amongst other idiomatic OS X apps. I’d liken the TextMate experience with a circle. It’s consistent and unsurprising, and I mean that in a good way!

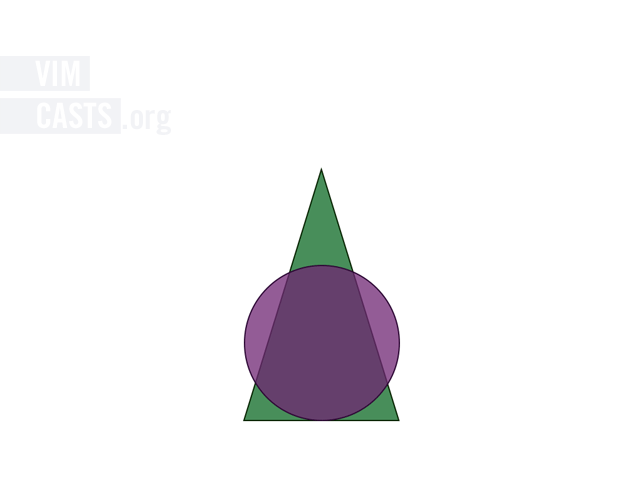

By contrast, the Vim experience is triangular. It doesn’t matter whether you’re used to working on OS X, Windows or Linux, the experience of using Vim isn’t going to feel like a natural fit with the conventions of the operating system. Vim has its own internal consistency. It feels more or less the same, no matter which environment it runs in.

Vim has sharp edges. If you’re not careful, you might cut yourself. But if you know how to wield it, you can exploit those sharp edges to slice through text effortlessly.

Vim can be configured to be more like other editors

Some plugins aim to recreate something of the TextMate experience for Vim users. These plugins attempt to trace a circle around Vim’s core:

If you’re used to TextMate, then this kind of setup allows you to stay inside your comfort zone while you find your bearings. Vim’s learning curve is famously difficult, so anything that helps the beginner to get a leg up is to be commended.

But I feel that this kind of setup prevents the user from learning The Vim Way. The interesting stuff happens in those sharp corners. If you stay in your comfort zone, you won’t discover them.

Superimposing a circle on the wedge makes the Vim experience resemble an axehead with a child-safety guard. If you are using the Janus Vim distribution, I am speaking to you.

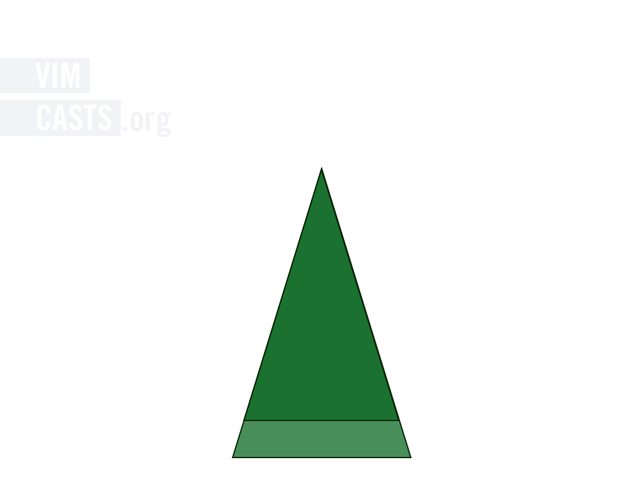

Plugins can extend Vim’s base

Some plugins extend Vim’s core functionality by strengthening its foundations:

Vim is designed to be extended. Many ‘core’ features are implemented in Vim script, rather than in C. These tend to be language specific features, such as syntax highlighting, indentation awareness, and omni completion. Out of the box, Vim provides syntax highlighting for hundreds of languages. You can browse the list by running :edit $VIMRUNTIME/syntax.

Vim ships with batteries included - plug-ins already plugged in - which means you can expect basic support when working with diverse file types. This provides a useful baseline, but it’s worth seeking out more up to date support for the languages that you use most frequently. For example, the vim-ruby plugin is maintained by members of the ruby community. It’s updated much more frequently than the Vim distribution, so if you do a lot of ruby work, you should get the latest release of vim-ruby from github.

Vim doesn’t support coffeescript out of the box, but you can install a plugin to enable syntax highlighting for .coffee files. If you’re doing a lot of work with coffeescript, then you’d be crazy not to install that plugin!

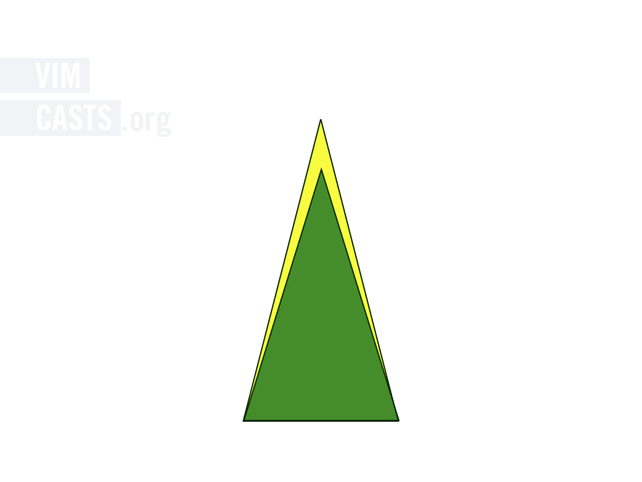

Plugins can sharpen the saw

Some plugins extend Vim’s core functionality by sharpening the saw:

This is my favorite category. These plugins use Vim’s core functionality as a reference point, then extrapolate by asking “what if…?”

When you know Vim’s capabilities, you’ll start to find yourself reaching for things that aren’t there. You’ll notice common patterns of usage, and realize that they could be streamlined if only Vim had an operator or motion for the job.

Vim’s commands are made to be combined. They follow a simple grammar: {operator}{motion}. That means that you can delete a word or paragraph by running daw or dap, just as you can yank a word or paragraph by running yaw or yap. If you add a custom operator command, then it should work with all the existing motions and text objects. If you add a custom text object, it should work with all existing operators.

Take the commentary.vim plugin, for example. It adds an operator command that toggles comments, and is mapped to \\{motion}. With that plugin installed, you can run \\ip to comment/uncomment the current paragraph.

Depending on how you format your code, a paragraph might happen to map to method definitions. But wouldn’t it be nice if there was a text object that mapped directly to your method definitions, regardless of how they were formatted?

For rubyists, the vim-ruby plugin has you covered. It adds text-objects for operating inside or around the current ruby method, with im or am. If you have both commentary.vim and vim-ruby installed, then you can comment out/in the current ruby method by pressing \\am. Use the . command to repeat.

Adding new operators and motions is like adding words to Vim’s vocabulary. The more words we have, the more ideas we can express.

Vim is a work in progress. You can view a list of feature requests by running :help todo. Try searching that document for ‘text object’, and you’ll see that a handful of text objects are on the road map. But why wait? You can have those features today if you install the appropriate plugins.

Know the saw, then sharpen it

In his classic essay, Seven habits of effective editing, Bram Moolenaar encourages us to invest time in sharpening the saw. Building your vimrc file and installing plugins are both ways of doing that, but it’s vital that you understand Vim’s baseline functionality before you build on top of it. First, learn to use the saw. Then sharpen it.

I’ve seen people customizing Vim in ways that blunt the saw. I’ve even seen people sharpening the wrong edge!

There’s more to Vim’s core functionality than you may realize. In my book, Practical Vim, I demonstrate all of the essential features of stock Vim. Learn to use vanilla Vim well, then you’ll be in a position to decide which plugins are a help, and which are a hindrance.

Post Script: what shape is emacs?

I presented these ideas at a lightning talk at the Scottish Ruby Conference. Emacs guru Jim Weirich was in the audience, and he made this sketch: